On his eighteenth birthday Leonard Peacock, four goodbye presents in tow, equips himself with his grandfather's P-38 WWII Nazi handgun and sets off for school to kill his best friend and then himself. Although I won't go into immense detail this analysis may contain spoilers - so if you're planning to read the book I wouldn't read on until you have.

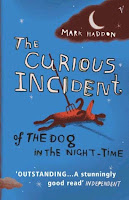

From the moment I started reading Matthew Quick's latest novel, Forgive Me, Leonard Peacock (FMLP), I felt like this was a book that I'd want to read over and over again. The first few chapters are an acclimatisation process because with this kind of first-person narration you are literally trying to inhabit someone's skull - adapt to their thought-process, way-of-speaking and so on. I personally relish immersing myself in the mind of characters like Leonard, Charlie from The Perks of Being a Wallflower and Holden from the Catcher in the Rye. It's something that I find a lot of in 'young adult' literature - though not all good quality. You'll also find a similar experience in Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher and The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time by Mark Haddon. These are narratives that specifically navigate, in some way, mental health and trauma. Third person narration can miss a trick in these situations.

From the moment I started reading Matthew Quick's latest novel, Forgive Me, Leonard Peacock (FMLP), I felt like this was a book that I'd want to read over and over again. The first few chapters are an acclimatisation process because with this kind of first-person narration you are literally trying to inhabit someone's skull - adapt to their thought-process, way-of-speaking and so on. I personally relish immersing myself in the mind of characters like Leonard, Charlie from The Perks of Being a Wallflower and Holden from the Catcher in the Rye. It's something that I find a lot of in 'young adult' literature - though not all good quality. You'll also find a similar experience in Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher and The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time by Mark Haddon. These are narratives that specifically navigate, in some way, mental health and trauma. Third person narration can miss a trick in these situations.

Any criticisms I have would be superficial and cosmetic - as well as a musing over the purpose of the 'Young Adult' genre. For example, the font is unnecessarily huge (from the point of view of quite serious subject matter) and the footnotes are a bit awkward to get used to at first. Jonathan Stevens makes some interesting points about Young Adult literature in The Alan Review (http://scholar.lib.vt.edu/ejournals/ALAN/v35n1/stephens.html). It's a genre which has a kind of stigma attached to it - Stevens highlights the 'certain negative assumptions from critics', it is accused of being 'simplistic', 'chick-lit', not literary, and cut off from 'bidding' for 'spots in the canon'. It is a process of categorisation which sometimes does genuine disservice to the material, putting adult readers off and restricting the readership. I made a similar point in relation to The Hunger Games which, rather than being the 'next Twilight' (?!?!) is actually an accomplished, thought-provoking dystopian novel. FMLP is about the 'young adult' or teenage experience but it is certainly not limited to it. Much of what Leonard encounters and goes through is not exclusively 'teenage'. A teenager taking a gun to school is topical in the states but the kind of pain and motivation for his potential actions is universal in our society.

Sona Charaipotra of Parade conducted an interview with Matthew Quick and asked whether his comfort zone lay in young adult fiction or adult fiction - he responded by saying he tries to 'write about people', to 'climb into their heads, whether they're 18 or 34'. The process is the same, regardless of marketing strategies so I don't think the adult market should be turned away from FMLP. (http://www.parade.com/60875/sonacharaipotra/silver-linings-playbook-author-matthew-quick-on-his-new-young-adult-novel-forgive-me-leonard-peacock)

One of the most crucial characters in the book is Herr Silverman, Leonard's high school Holocaust Studies teacher.

'Most teachers refuse to close the door when they are alone with a student, saying it's against the law or something, which is pretty stupid. It's like everyone thinks teenagers are about to get raped every second of the day and that an open door can protect you. (It can't. how could it?) But Herr Silverman closes the door, which makes me trust him. He doesn't play by their rules, he plays by the right rules.' (115)

'We sort of lock eyes and I think about how Herr Silverman is the only person in my life who doesn't bullshit me, and is maybe the only one at my school who really cares whether I disappear or stick around.' (120)

Herr Silverman tells Leonard to call him if he ever thinks about taking his own life, and unbeknownst to him the simplest of his actions make the most profound difference. He certainly exceeds his 'professional' role but views it as extenuating circumstances. Which they are, even if it's probably easier to not get involved. Of all the people in Leonard's life he is the one to pick up the signals and act on them. In a GoodReads interview (https://www.goodreads.com/interviews/show/885.Matthew_Quick), Quick was asked about Herr Silverman's role in Leonard's story and I think his response is very important:

"MQ: Whenever there is a school shooting, we ask what's wrong with schools, teachers, young people, and society at large—reasonable questions in the wake of tragedy. But as a former high school teacher who once counseled troubled teens on a daily basis, I find it upsetting that we don't ask what's going right in schools whenever a student in crisis is given the help he or she needs and doesn't end up committing an act of violence, which is every single day. Going above and beyond seldom results in praise or rewards for teachers, but many do it anyway. If you really care about teens and are willing to do the emotional work necessary to help them through the maturation process, there is no harder job than that of a high school teacher."

Leonard's neighbour, Walt, is also a key figure. He spends his days inside watching Humphrey Bogart movies but his constancy is clearly something that Leonard values and something he can't find in people his own age (Walt is a widower). They communicate through movie quotes, managing to say a lot to each other in a language they both understand but with a restricted nature that can also not reveal the full extent of what is going on in Leonard's mind. Leonard gives each present to the four people who have inspired him, in the smallest ways and even without knowing or caring - the ones who gave him moments of value. With his parents very much out of the picture emotionally (an absentee father and a horrifically narcissistic mother who spends her time away with her new boyfriend), Leonard is very much alone with his thoughts. His mother will not let him have therapy because she refuses to 'let any therapist blame his problems on her'. Which kind of sums up his family life.

Leonard's neighbour, Walt, is also a key figure. He spends his days inside watching Humphrey Bogart movies but his constancy is clearly something that Leonard values and something he can't find in people his own age (Walt is a widower). They communicate through movie quotes, managing to say a lot to each other in a language they both understand but with a restricted nature that can also not reveal the full extent of what is going on in Leonard's mind. Leonard gives each present to the four people who have inspired him, in the smallest ways and even without knowing or caring - the ones who gave him moments of value. With his parents very much out of the picture emotionally (an absentee father and a horrifically narcissistic mother who spends her time away with her new boyfriend), Leonard is very much alone with his thoughts. His mother will not let him have therapy because she refuses to 'let any therapist blame his problems on her'. Which kind of sums up his family life.

There are moments in this book that really stand out. Quick has masterfully created Leonard as character and as voice - his inner monologues contain things we would never admit we are thinking, or do not realise we have within us - he unleashes these built-up incisive and scything streams of perception. Sentence after sentence mounts into a pulsating sensation which is relentlessly honest and, at times, shocking. It's a kind of cathartic anger which is written in a tone and style that borders on charming and humorous in a dark sort of way. Dressed in what he calls his 'funeral suit' Leonard often joins the procession of commuters and 'suits' going to work each day. These people, a vast collective - commuting every day and every night, for their whole lives. To Leonard, it is the most terrifying thing to observe. He chooses one to follow, to discover if there is something to be optimistic about in the future.

“The whole time I pretend I have mental telepathy. And with my mind only, I’ll say — or think? — to the target, 'Don’t do it. Don’t go to that job you hate. Do something you love today. Ride a rollercoaster. Swim in the ocean naked. Go to the airport and get on the next flight to anywhere just for the fun of it. Maybe stop a spinning globe with your finger and then plan a trip to that very spot; even if it’s in the middle of the ocean you can go by boat. Eat some type of ethnic food you’ve never even heard of. Stop a stranger and ask her to explain her greatest fears and her secret hopes and aspirations in detail and then tell her you care because she is a human being. Sit down on the sidewalk and make pictures with colorful chalk. Close your eyes and try to see the world with your nose—allow smells to be your vision. Catch up on your sleep. Call an old friend you haven’t seen in years. Roll up your pant legs and walk into the sea. See a foreign film. Feed squirrels. Do anything! Something! Because you start a revolution one decision at a time, with each breath you take. Just don’t go back to that miserable place you go every day. Show me it’s possible to be an adult and also be happy. Please. This is a free country. You don’t have to keep doing this if you don’t want to. You can do anything you want. Be anyone you want. That’s what they tell us at school, but if you keep getting on that train and going to the place you hate I’m going to start thinking the people at school are liars like the Nazis who told the Jews they were just being relocated to work factories. Don’t do that to us. Tell us the truth. If adulthood is working some death-camp job you hate for the rest of your life, divorcing your secretly criminal husband, being disappointed in your son, being stressed and miserable, and dating a poser and pretending he’s a hero when he’s really a lousy person and anyone can tell that just by shaking his slimy hand — if it doesn't get any better, I need to know right now. Just tell me. Spare me from some awful fucking fate. Please.”

Woven into the narrative are chapters that are letters from future characters to Leonard. This revealed to be a process which Leonard started under Herr Silverman's tutelage - of writing letters from your future self - reasons to keep on going - telling you it will be worth it. Leonard sets his in a sort of post-apocalyptic future - with is kind of apt because his eighteenth birthday is built up as a personal apocalypse. They don't always offer him comfort but they are something - even if it only helps him to learn to value himself a little more.

Leonard's voice is captivating, frightening, and familiar. His story is moving for all that is unsaid and only implied. There are some dramatic and traumatic revelations towards the end of the book, which are done subtly and sensitively but they are very heavy subject matter. The ending is open, there is little obvious resolution - but you can't ask things like this to resolve. It's not as straightforward as a happy ending, or even a definitive decision. The note it ends on is both bleak and heartbreaking but also optimistic. Leonard got through his birthday - even if only by accident, and that's a great ending for me - a small miracle. Each breath could be a revolution, literally, of life.Throughout the whole day he seems to be wishing, deep down, to wish him happy birthday - even if they don't know - to give him a reason not to do what he's planning to do.

"I'm trying to let him know what I'm about to do.

I'm hoping he can save me, even though I realize he can't.”

The few decent people might be enough in the face of the 'ubermorons' but it's not certain. No one can really offer any reassurances. It's luck that Leonard survives but simultaneously a choice he is making if he gets through another day - even if he gets very little reward for doing so. Are his circumstances going to change? There's no promise of that. Is he going to get better? We don't know. There are no guarantees. But on his eighteenth birthday Leonard discovered he has a teacher who would go above and beyond for him and a neighbour who would miss him, and for that day - that's enough.

More quotes:

“There's a lot for you to live for. Good things are definitely in your future, Leonard. I'm sure of it. You have no idea how many interesting people you'll meet after high school's over. Your life partner, your best friend, the most wonderful person you'll ever know is sitting in some high school right now waiting to graduate and walk into your life - maybe even feeling all the same things you are, maybe even wondering about you, hoping that you're strong enough to make it to the future where you'll meet.” "I'm trying to let him know what I'm about to do.

I'm hoping he can save me, even though I realize he can't.”

The few decent people might be enough in the face of the 'ubermorons' but it's not certain. No one can really offer any reassurances. It's luck that Leonard survives but simultaneously a choice he is making if he gets through another day - even if he gets very little reward for doing so. Are his circumstances going to change? There's no promise of that. Is he going to get better? We don't know. There are no guarantees. But on his eighteenth birthday Leonard discovered he has a teacher who would go above and beyond for him and a neighbour who would miss him, and for that day - that's enough.

More quotes:

'Different is good. But different is hard. Believe me, I know.' (121)

'I realised that the truth doesn't matter most of the time, and when people have awful ideas about your identity, that's just the way it will stay no matter what you do.' (57)

N.B. Seamus Heaney, truly one of the great poets of all time, died today. His work will undoubtedly live on, not just as canonical works in our school textbooks but as affecting individual poems in their own right which can be come to at any stage in life. He will be missed.

To read a few go to http://www.poemhunter.com/seamus-heaney-3/